PART I

INTRODUCTION

According to the coalition agreement of the Luxembourg Government 2023-2028 (p. 100):

“The cultivation of cannabis for personal use as it was legally regulated will be maintained. The Government will observe the position of the three neighbouring countries on the legalisation of cannabis.”

Although classed in the most restrictive schedules by the United Nations Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs of 1961,[1] at a time when little was known about its components and mechanisms of action, cannabis is still the most widely used illegal psychoactive drug in the world, including the European Union. Luxembourg is no exception. In fact, the latest estimates of the prevalence of cannabis use in the general population outline the following situation in Luxembourg:

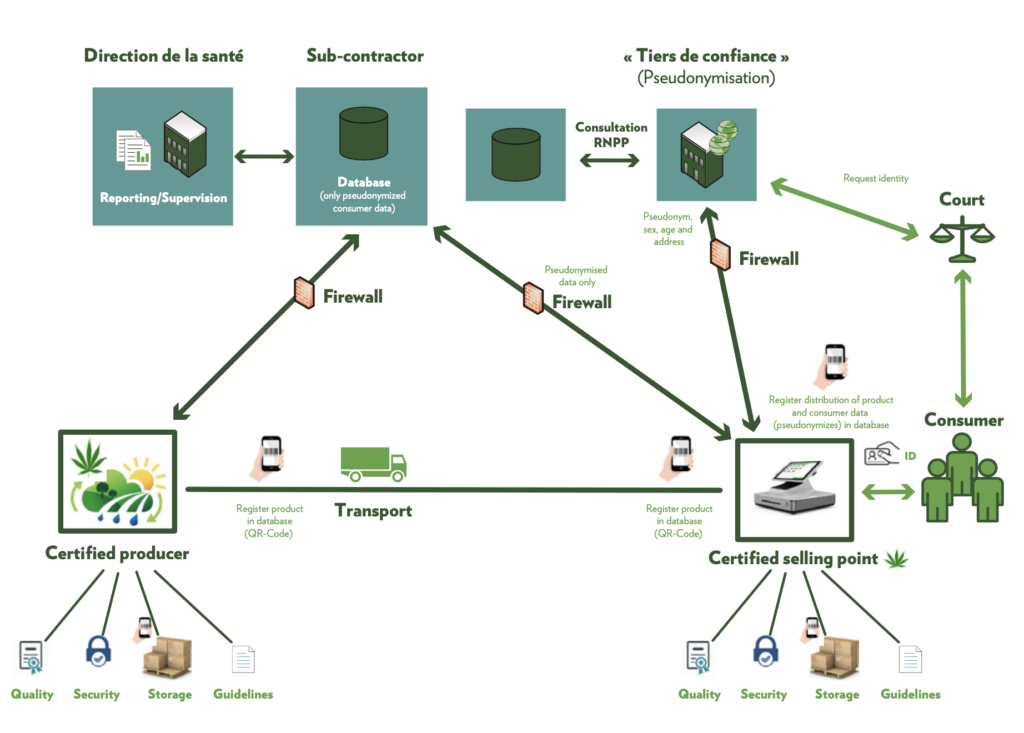

Fig. 1a: National lifetime, 12-month and 30-day prevalence of cannabis use in different age groups (% valid) (EHIS, 2019)

Source: European Health Interview Survey (EHIS), Luxembourg 2019, data processed by the Luxembourg National Focal Point of the EMCDDA

Lifetime prevalence of cannabis use (use at least once in a lifetime) is highest in young adults (15-34 years). Last-year and last-30-day prevalence in 15-18-year olds is, however, higher than that of older age groups and shows an upward trend (Figure 1a). The rate of prevalence, specifically over the last month is, however, one of the indicators of higher-risk use.

In contrast, the higher levels of lifetime prevalence of cannabis use compared to last 12-month or last-30-day prevalence indicate that most young people aged 15-34 who used cannabis did so experimentally or infrequently rather than regularly or continuously.

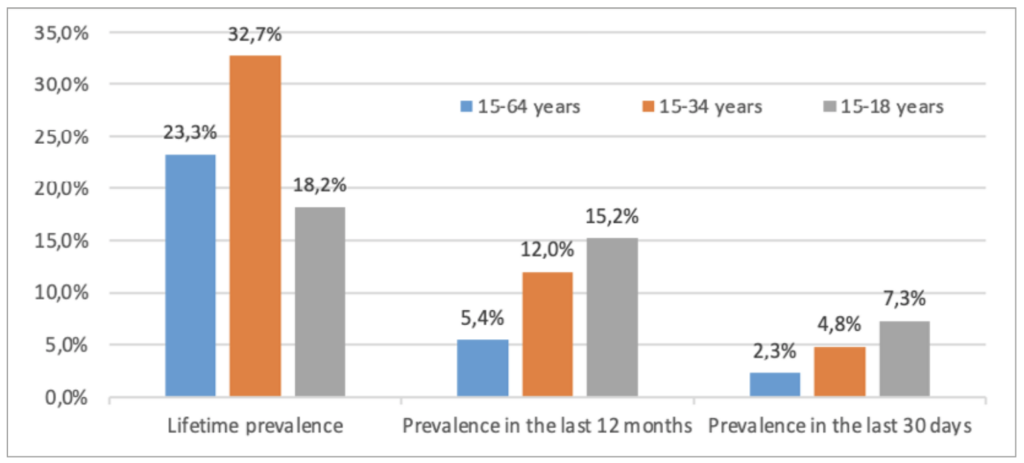

Although comparison of 2014 and 2019 data suggests an increase in cannabis use in all age groups (Figure 1b), these differences are not statistically significant:

- Experimental (lifetime) cannabis use in young adults (15-34 years) rose to 32.7% in 2019. Lifetime use in young people (15-18 years) increased from 16.6% in 2014 to 18.2% in 2019.

- Last-year cannabis use in the general population has increased since 2014. This increase was observed in young adults (15-34 years), and particularly in the youngest cohort (15-18 years).

- Last-month cannabis use shows an increase between 2014 and 2019, particularly in the youngest users (15-18 years), from 4.7% in 2014 to 7.3% in 2019.

Fig. 1b: Comparison of lifetime, last-year and last-month prevalence of cannabis use by different age groups (% valid) (EHIS, 2014, 2019)

Source: European Health Interview Survey (EHIS), Luxembourg 2014, 2019, data processed by the Luxembourg National Focal Point of the EMCDDA

Source: European Health Interview Survey (EHIS), Luxembourg 2014, 2019, data processed by the Luxembourg National Focal Point of the EMCDDA

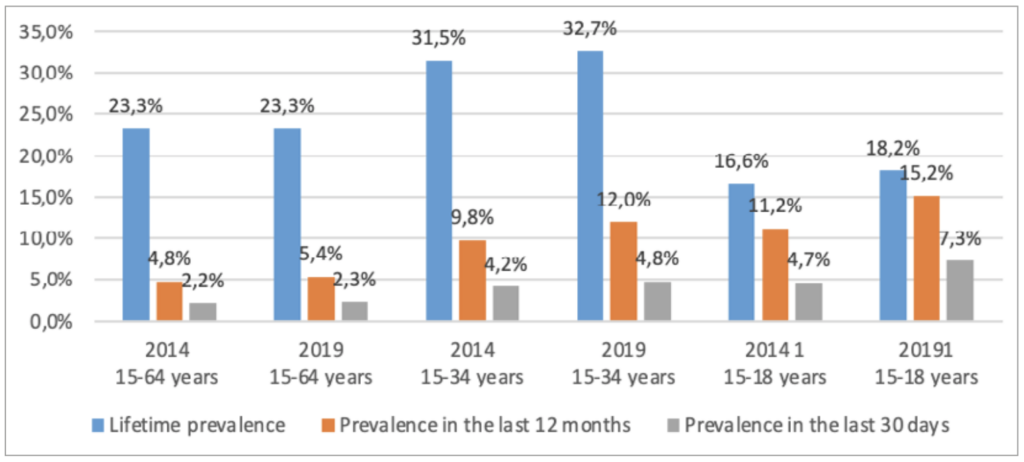

Gender differences are also worth noting. According to the latest estimates of the prevalence of cannabis use in the general population (EHIS 2014 and 2019), a higher proportion of men report having used cannabis than women(in their lifetime, as well as in the previous year and previous month). For example, in 2019, the prevalence of last-month cannabis use in men was more than double the prevalence of cannabis use in women (Figure 1c).

Fig. 1c: Prevalence of lifetime, last-year and last-month cannabis use in men and women: comparison of 2014 and 2019 data (EHIS, 2014, 2019)

Source: European Health Interview Survey (EHIS), Luxembourg 2014, 2019, data processed by the Luxembourg National Focal Point of the EMCDDA

Source: European Health Interview Survey (EHIS), Luxembourg 2014, 2019, data processed by the Luxembourg National Focal Point of the EMCDDA

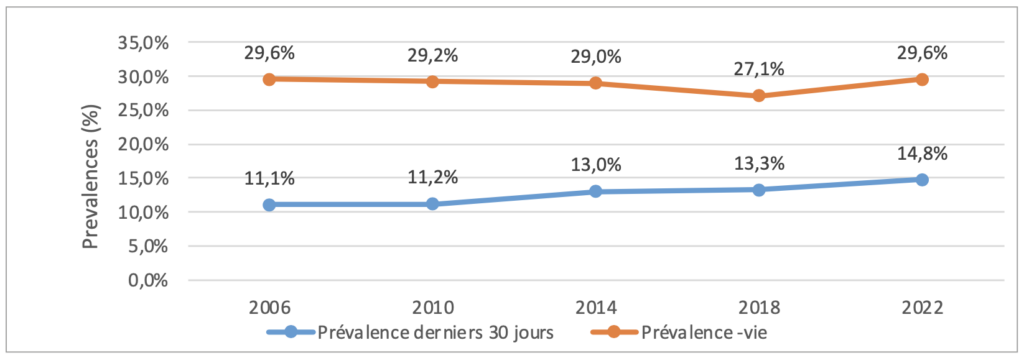

The results of the 2022 “Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC)” study show that the lifetime prevalence of cannabis use in young people aged 15 to 18 years hardly changed at all between 2006 and 2022. Overall, the proportion of adolescents who report having used cannabis in their lifetime has remained stable. However, the proportion of adolescents who have used cannabis in the last 30 days has increased (see Figure 2a). Overall, in 2022, 13% of girls and 16% of boys aged 15 to 18 reported having used cannabis in the last 30 days (2018: 10% of girls and 16% of boys).

Fig. 2a: Lifetime and last-month prevalence of cannabis use in adolescents aged 15-18 years (% valid) (HBSC, 2006-2022)

Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) Luxembourg, 2006-2022

Source: Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) Luxembourg, 2006-2022

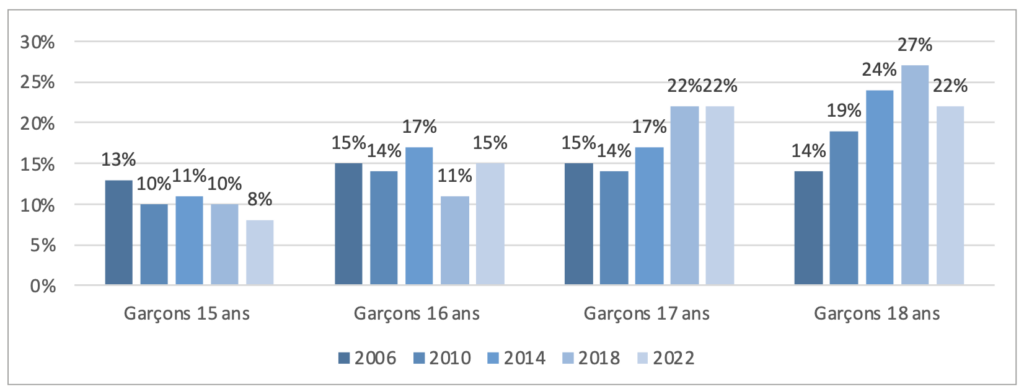

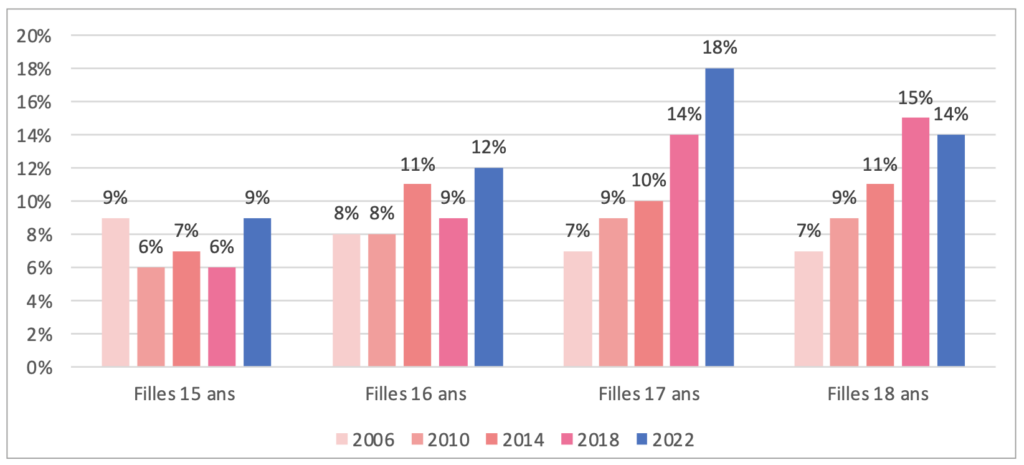

Analysis by age group reveals the following trends: in 2022, the percentage of girls and boys aged 17 to 18 who reported having used cannabis in the last 30 days increased compared to 2006. In 18-year-old girls, for example, this percentage doubled from 7% to 14% over the period. By contrast, in 15-year-old girls, the percentage remained stable at 9% (dropping from 13% to 8% for boys) (Figures 2b and 2c). Both indicators of cannabis use (lifetime and last 30-day prevalence) suggest that use has decreased in the youngest adolescents (15 years) and increased in older adolescents, especially in girls.

Source: HBSC study, Luxembourg (University of Luxembourg, 2022)

Source: HBSC study, Luxembourg (University of Luxembourg, 2022)

Source: HBSC study, Luxembourg (University of Luxembourg, 2022)

Source: HBSC study, Luxembourg (University of Luxembourg, 2022)

Even though cannabis is illegal, and despite the steps taken to prevent it being sold and used, cannabis is currently the most widely used psychoactive substance by young and not-so-young people.

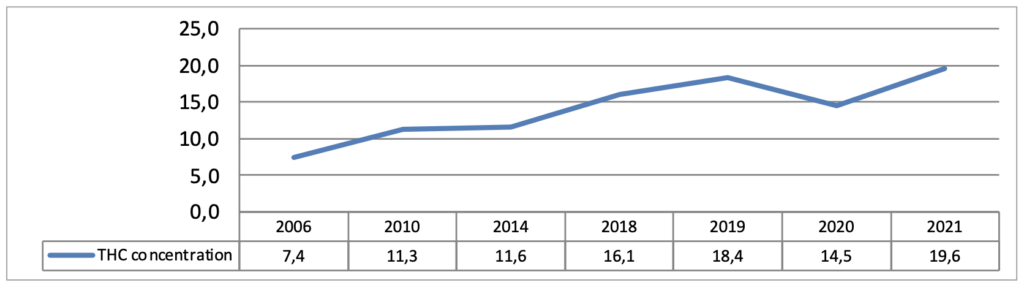

In addition, the purity, i.e. the Δ-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC[2]) concentration in the various types of cannabis currently available on the black market, is steadily increasing. Since 2006, this concentration has doubled in the EU and Luxembourg. Cannabis seized in Luxembourg (resin and herbal, among others) in 2019 showed an average THC concentration of 18.4%; in 2021, an average THC concentration of 19.6% was found (Figure 3). When only cannabis products with a THC concentration of 1% or more are considered, the overall average purity of cannabis-based products reaches 20.8% in 2021. It is also worth noting that 22.4% of cannabis (mainly in the form of resin)seized in Luxembourg in 2021, 10% in 2020, 19% in 2019, and 16% in 2018, showed a THC concentration of more than 30%.[3],[4]

Also, an emergence of products with a high concentration of THC and a low content of cannabidiol (CBD), a molecule with no euphoric effect, was observed. These high THC concentrations represent an increased health and addiction risk. Unlike THC, the average CBD concentration in cannabis has been falling constantly since the early 2000s, leading to an imbalance between the THC and CBD concentrations in the drug.

Source: Luxembourg National Health Laboratory, data processed by the Luxembourg National Focal Point of the EMCDDA, 2021

Source: Luxembourg National Health Laboratory, data processed by the Luxembourg National Focal Point of the EMCDDA, 2021

The highest THC levels in cannabis currently availably on the black market continue to break all-time records, in particular owing to increasingly refined extraction techniques and new varieties being cultivated. THC concentrations of 36 to 60% in various cannabis derivatives and extracts were recorded in 2019. In 2020, the maximum THC concentration observed in cannabis products was 72.7%, rising to an all-time high of 98.4% in 2021.[5]

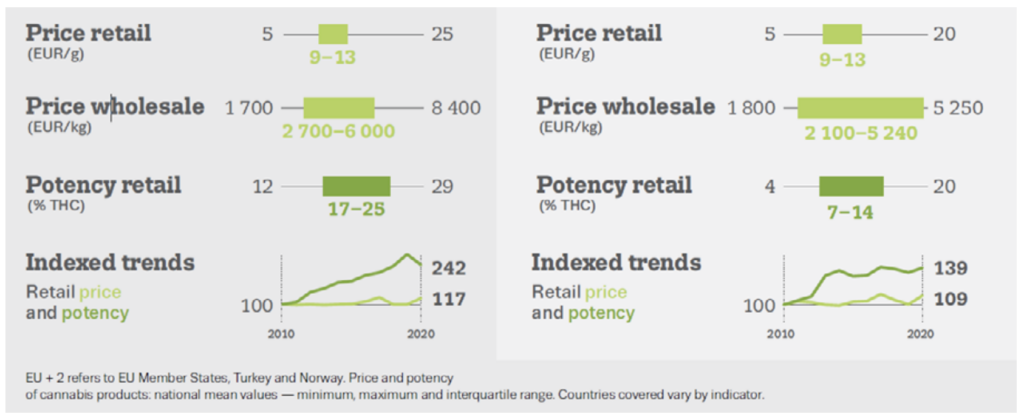

In addition, the trend in THC concentrations, in relation to the price of cannabis products currently on the market, raises questions. The THC concentration of cannabis sold on the black market more than doubled between 2010 and 2020, while the price in Europe remained relatively stable over the same period (Figure 4).

Fig. 4: Average change in price and concentration of flowering tops in the EU (cannabis resin on the left, flowering tops on the right:

Source: European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA, 2022)

Source: European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA, 2022)

According to a sample of recreational drug users surveyed by the European Web Survey on Drugs (EWSD),[6]conducted in Luxembourg in 2018, cannabis prices averaged €14.5/g for resin and €16.7/g for herbal cannabis. The results of the latest EWSD conducted in Luxembourg in 2021 show that cannabis prices on the black market have fallen sharply to €9.0/g for resin and €10.1/g for herbal cannabis.[7]

In Luxembourg, the number of people in contact with specialist drug and addiction services due to their high-risk use of cannabis seems to have increased over the last few years, which may be linked, amongst other things, to the increased concentration of THC in cannabis products sold on the black market.[8]

In addition, most users are accustomed to smoking cannabis mixed with tobacco, a method of taking the drug that carries additional, and proven, health risks due to the combustion of various harmful substances and the risk of nicotine addiction.

To date, the quality of cannabis taken by the national population is driven by the black market. The cannabis sold on the black market is often adulterated and contains a wide variety of cutting agents (wax, soil, henna, paint, sand, talc, aromatic hydrocarbons, other herbs, pollen, microscopic glass beads, lead, etc.), many of which present an additional and significant health risk to users. In addition to these cutting agents, there are also risks of contamination with pesticides, microbes, heavy metals or even fungi.

Cannabis users are at the mercy of the criminal organisations that control the black market, where they also risk becoming victims of aggressive behaviour and of encountering other higher risk substances. Users break the law when they obtain cannabis which, in addition, is of uncertain quality and generates substantial revenue for organised crime, which has seen its power and growth margins increase considerably. This situation not only exposes users to increased health and safety risks, but also impacts on wider society. Illegal selling of cannabis in public places is increasingly perceived by the general public as alarming and disturbing.

A longitudinal analysis shows a further increase in the quantities of cannabis intended for the domestic market seized from 2014 onwards, with a new high in the amount of cannabis seized in 2019. In 2020 and 2021, the number of seizures (2021: 1,150 seizures; 2020: 1,142 seizures; 2019: 1,315 seizures) remained stable, although the quantities seized (2021: 53.3 kg; 2020: 102 kg; 2019: 371 kg) were down on 2019, but are still high and reflect the well-established presence of cannabis on the Luxembourg black market for drugs. Overall, seizures of cannabis-based products accounted for 74.1% of the total number of seizures in Luxembourg in 2021 (2020: 67.2%; 2019: 70.1%).[9] It is, however, worth noting that variations in drug seizures may also depend on the intensity of policing over a given period.

The present-day context of cannabis use is also based on the considerable change in the image of cannabis and its perception by the general public. Increased research into the composition and properties of cannabis and, in particular, the growing recognition of the use of cannabis for medical purposes, have contributed to this change of perception. This change has also taken place in Luxembourg, where the medical use of cannabis has been permitted under certain conditions since the entry into force of the Act of 20 July 2018[10] and its implementing regulations.

In addition, some jurisdictions have already legalised and regulated access to non-medicinal cannabis, including Canada, Uruguay and many US states, although practical implementation in these countries and states often differs. In addition to these countries and jurisdictions, many other countries are currently engaged in discussions and work on regulating access to non-medical cannabis, such as Germany, the Netherlands, the Czech Republic, Malta, Colombia, Costa Rica, Mexico, New Zealand, Jamaica, Israel and South Africa. In these countries, the search for alternative and sustainable models and approaches is based on the lessons learned from the inadequacy of some current legislative approaches to the sale and use of cannabis when compared to their intended purpose and on a desire to provide a regulatory framework for a widespread and growing phenomenon that is clearly resistant to law enforcement measures. In fact, approaches and regulations adopting prohibition, law enforcement and punitive responses as basic principles have not delivered the desired results in many countries.

The pilot project for legal access to cannabis for non-medical purposes is similar to regulations adopted to deal with the dangers of alcohol or tobacco use. In fact, it can be argued that it is the government’s responsibility to regulate and minimise the risks associated with products or substances that are taken by a significant proportion of the population and whose use is potentially high risk. The idea that the prohibition of alcohol and/or tobacco would be an appropriate, reasonable and effective solution to preventing the use and/or abuse of these psychoactive substances, some of which, like alcohol, are known to be more harmful than cannabis,[11] has never been seriously considered by European governments in recent decades. An exclusively punitive approach is, therefore, open to criticism.

In addition, the pilot project envisaged by Luxembourg is in line with the national approach generally taken in the field of drugs and addiction, which for two decades now has recognised the worth of harm- and risk-reduction measures in relation to drugs and addiction. The pilot project for legal access to cannabis for non-medical purposes is, therefore, just an extension of a public healthcare and public order rationale and a risk- and harm-reduction approach that has now been legitimised in lots of European countries and, in addition, is advocated by the European Union[12].

Existing global models for regulating access to cannabis for non-medical purposes differ insofar as they take into consideration national differences and characteristics in order to arrive at appropriate and effective solutions. Luxembourg will, therefore, have to adopt a national approach that takes into account its own cultural, social and economic parameters.

In view of the proposed regulation of cannabis for non-medical purposes announced by the Government of Luxembourg on 22 October 2021, in particular, as a first stage in a package of measures on the problem of drug-related crime, data allowing for a proper and nuanced assessment of the situation regarding cannabis and its use are required.

It is worth noting that this is an empirical approach, given that the national pilot project will be subject to scientific evaluation based on relevant impact indicators, which are key to adapting and developing the pilot project to meet requirements in the territory of Luxembourg. This scientific evaluation will be carried out in close collaboration with the EMCDDA and its National Focal Point, and with various public health research institutions. In addition, and as part of a more general evaluation, reports will be prepared describing the situation before the law comes into force and at regular periods thereafter. To this end, studies will be conducted in collaboration with research institutions and with the support of the EMCDDA, to assess specific indicators related to the implementation of the pilot project for legal access to cannabis for non-medical purposes.

A goal-oriented evaluation of the changes observed as a result of the future regulation presupposes that the relevant data have been collected before the law comes into force (baseline) and then at regular intervals during the rollout of the new measures.

To this end, a “Scientific Evaluation” working group was set up to compile a set of relevant indicators and the overall architecture of the evaluation exercise. In the first instance, national objectives were clearly defined in order to determine the relevant indicators.

[1] In the United Nations Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs of 1961, cannabis is listed in Schedules I and IV alongside substances like heroin, desomorphine, etc.

[2] European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA): The main psychoactive ingredient in all cannabis-based products is Δ9- tetrahydrocannabinol.

[3] Luxembourg National Health Laboratory. (2021). 2006-2021 data on the purity of illegal psychoactive substances processed by the EMCDDA Luxembourg Focal Point. Luxembourg: Luxembourg National Focal Point of the EMCDDA, Department of Epidemiology and Statistics at the Directorate of Health.

[4] In 2019, 22.4% of samples had a THC concentration above 30%.

[5] Luxembourg National Health Laboratory (2021) 2021 data on the purity of illegal psychoactive substances processed by the EMCDDA Luxembourg Focal Point. Luxembourg: Luxembourg National Focal Point of the EMCDDA, Department of Epidemiology and Statistics at the Directorate of Health.

[6] Trend data not available.

Berndt, N., & Seixas, R. (2019). Enquête Européen sur les Drogues au G.D. de Luxembourg 2018. EMCDDA Luxembourg Focal Point, Epidemiology and Statistics Department, Health Directorate: Luxembourg.

[7]Kugener, T., Berndt, N. & Seixas, R. (manuscript in preparation). Enquête Européen sur les Drogues au G.D. de Luxembourg 2021. Luxembourg National Focal Point of the EMCDDA, Department of Epidemiology and Statistics at the Directorate of Health: Luxembourg.

[8] Berndt, N., Seixas, R., Origer, A. (2021). National Drug Report 2021 (Rapport RELIS) – The drug phenomenon in the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg: Trends and Developments, Epidemiology and Statistics Department, Directorate of Health: Luxembourg.

[9] Luxembourg Judicial Police Service – Drug Squad (2021) Data on drug seizures processed by the EMCDDA Luxembourg Focal Point. Luxembourg: Luxembourg National Focal Point of the EMCDDA, Department of Epidemiology and Statistics at the Directorate of Health.

[10] Luxembourg Ministry of State – Central Legislative Service (2018) Act of 20 July 2018 amending the amended Act of 19 February 1973 on the sale of medicinal substances and the fight against drug addiction. Publication: 01/08/2018; Effective date: 05/08/2018. Luxembourg: Ministry of State – Central Legislative Service. Available at: http://data.legilux.public.lu/eli/etat/leg/loi/2018/07/20/a638/jo

[11] Nutt, D., King, L.A., Saulsbury, W., Blakemore, C. (2007). Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse. The Lancet, 369(9566):1047-53. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60464-4.

[12] Council of the European Union (2003). Council Recommendation of 18 June 2003 (2003/488/EC) on the prevention and reduction of health-related harm associated with drug dependence, OJ 3.7.2003, L 165/31. Brussels: Official Journal of the European Union. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2003:165:0031:0033:EN:PDF

Clearly, the pilot project for legal access to cannabis for non-medical purposes should not aim to promote, or even to normalise or trivialise its use, but rather to make it possible to scientifically assess whether managing its use for non-medical purposes will reduce associated risks and harm, remembering that cannabis use has been going on for decades, despite its illegality.

The working group believes that the proposed pilot project can help to develop an evidence-based scientific foundation for decisions on possible future changes to the law. The evidence obtained from a scientific assessment (see II.3) should be methodologically sound, leading to scientifically valid knowledge as well as contributing to the objectivity of the debate and future orientations.

A scientific experiment (pilot project), limited in time and scope, is believed to be the most appropriate way to achieve the objectives sought, as described below.

An approach with public health at its core

The health of users of cannabis obtained on the black market is exposed to increased risk. As described above, in the course of the last 15 years, the THC content of cannabis and related products has significantly increased, while their CBD content has been significantly reduced; their price, meanwhile, has remained relatively stable (see Fig. 6). The quality of cannabis available on the black market is unpredictable (impurities, THC concentration, pesticides, adulterants, etc.) and there is a complete lack of any reliable way for users to determine, in particular, the THC and CBD content of products bought illegally.

Given that the potential harm associated with cannabis use is greater early on in life and/or with frequent use, the working group recommends that the government’s primary public health objectives should be as follows:

- To ensure product quality (THC and CBD content, absence of impurities and contamination, cutting agents, etc.) and product safety (e.g. plain packaging, warning labels), so that users know what they are taking and are able to make informed choices.

- To reduce high-risk use and addiction.

- To reduce the frequency and intensity of cannabis use, in particular cannabis with high THC and low CBD concentrations.

- To reduce the prevalence of high-risk methods of use (e.g. smoking cannabis with tobacco).

- To increase the age at which people start using cannabis.

- To protect young people by bolstering preventive measures and reducing cannabis use.

- To reduce the attractiveness and prevalence of synthetic cannabinoid use.

To use evidence-based information, education, health promotion and prevention strategies (universal, indicated, selective and environmental):

- To raise public awareness of the potential risks and damage to physical and mental health and to societylinked to cannabis, in particular, relating to regular high-risk use.

- To inform the public of the variability of cannabis quality, of the psychoactive effects of cannabis use and of the importance of concentrations, in particular, THC and CBD content.

- To bring about cannabis use that is more responsible, by providing information on the risks associated with the different frequencies/intensities of cannabis use.

- To promote methods of taking cannabis that are less damaging to health, particularly in view of the widespread habits in Luxembourg of smoking it with tobacco or of using it at the same time as drinking alcohol.

- To raise users’ awareness of the risks associated with using multiple psychoactive substances at once.

- To make users aware of their responsibilities and enhance their decision-making skills so that they can make informed choices, with a view to achieving a change in attitudes and behaviours towards less risky methods of taking cannabis, and of the fact that the lowest-risk type of behaviour in this area is abstinence. Raising awareness of the potential risks of the cannabis varieties used, as well as specific labelling of THC and CBD content and a colour-coded risk score, could help to achieve this objective.

- To increase the availability of and access to prevention programmes and risk-reduction services, in particular for socially disadvantaged groups and young people.

- To increase the availability of appointments and access to out- and in-patient treatment for the various target groups.

In addition to the above-mentioned public health objectives, other objectives include:

- To reduce the risks associated with the currently unavoidable exposure of users to the dangers associated with acquiring cannabis on black markets.

- To reduce social risks by helping to prevent users from entering the justice system (criminalisation, stigmatisation, etc.) and by keeping users away from the black market and criminal networks.

- To fight crime on the supply side, reducing the profit-generating activities of organised crime and helping to dry up an underground economy linked to drug trafficking, given that the revenue generated by the black market currently fuels the power of organised crime, increases its room for manoeuvre and aids its growth. These conditions, created by, among other things, the black market, can encourage the emergence and proliferation of societies and organisations in no-go areas that are detrimental to social cohesion and inclusion.

- To free up capacity and resources to reduce supply and use an approach less focused on punishment, thereby relieving police forces and the courts of the burden of prosecuting minor drug offences so that available resources can be focused on increasing the fight against organised crime.

- To closely monitor cannabis use at the national level to better understand patterns and trends of use in different population groups and to ensure the collection of longitudinal, comparable and nuanced data. These data will also make it possible to assess the impact of the pilot project for legal access and to make adjustments, as well as contributing, in the long term, to proactive investment in an integrated public health initiative that prioritises prevention and treatment. The data collected will also enable Luxembourg to contribute to international scientific literature on cannabis markets, cannabis use, public health implications and the potential consequences of legislative change.

- To develop pricing policies to discourage the use of cannabis with high THC content and increased health risks. The end price should, therefore, better reflect the potentially higher risks and harms of these cannabis products for users and for society.

1.4.1 For international and European law

As far as international law is concerned, the current international control and classification system for narcotic drugs was established by the United Nations Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs of 1961. This system currently comprises three conventions (to which Luxembourg is a party), namely:

- the United Nations Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs of 1961, as amended by the 1972 Protocol;

- the Convention on Psychotropic Substances of 1971;

- the United Nations Convention against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances of 1988.

The protection of public health and well-being is at the heart of international and European drug legislation. Luxembourg has always pursued these same objectives and does not intend to deviate from this paradigm with this pilot project. Following a long-standing national policy of cracking down on cannabis use and promoting addiction prevention, and in view of the poor results achieved by the punitive approach, Luxembourg wishes to launch a pilot project that addresses the social phenomenon of large-scale cannabis use in the general population. International instruments give national legislators some leeway in determining the measures needed to implement obligations, and do not preclude trials for scientific purposes. This temporary and reversible scientific pilot project is, therefore, in line with the logic, and general spirit, of the international conventions. The pilot project’s precise relationship with international and European law will depend on the specific scope of the legal framework, its implementation and the legislative impact analysis.

It is worth noting that some regions of the world have seen a shift in opinion, with new approaches, on how to regulate access to cannabis. For this reason, with regard to international legislation, lines of communication will have to be kept open with other countries opting for a policy similar to that of Luxembourg, as well as with international organisations with expertise in this field. Within this context, the 2019 WHO recommendations on the reclassification of cannabis and related substances should also be taken into consideration.[1] At the same time, Luxembourg will have to keep dialogue open with the European Commission and neighbouring countries to inform them of the national impact of the pilot project. Further analysis is needed on how a pilot project on access to cannabis for non-medical purposes would fit with EU and international law, and on the development of a multi-dimensional communication strategy.

In any event, Luxembourg will maintain its commitment to the importance of the rule of international law, and in general, to multilateralism.

In this spirit, many bilateral and multilateral consultations and exchanges have taken place and will continue to be developed.

1.4.2 In terms of epidemiology and public health

Increased prevalence of cannabis use

It cannot be ruled out that legal access to cannabis will lead to temporary or sustained increases in cannabis use, or even tobacco use, for those who use smoke cannabis with tobacco. In line with the public health approach recommended, particular importance should, therefore, be attached to the measures that need to be taken to prevent a possible increase (whether temporary or persistent) in the prevalence and frequency of cannabis and tobacco use, especially in young people. Particular emphasis should, therefore, be placed on information, education and awareness-raising measures for the various target groups.

It is key to note that the still small number of studies on the effects of legalisation measures regulating access to non-medical cannabis provide mixed and inconclusive results.[2][3]Many factors are at play, and may be substantially influenced by higher rates of monitoring and testing. In addition, the importance of prevalence of use as an indicator of the impact, or even the merits, of drug policy is often overestimated, to the detriment of equally, or even more important indicators, such as high-risk use or the impact of such use on users’ mental health.

Even with robust longitudinal data it is, therefore, difficult to know what the drivers of change are and, in particular, to what extent any change in policy or legislation is material, causal or merely consequential.

In any event, these findings must be qualified insofar as the Luxembourg context differs from that of other jurisdictions. Some of these other jurisdictions, such as Canada, Uruguay, and some US states, have only recently started to evaluate the effects of legislation regulating access to cannabis for non-medical purposes. Most of these jurisdictions have only recently adopted legislation legalising access to cannabis for non-medical purposes. It would, therefore, be premature to draw definitive conclusions on their impact on public health indicators.

Some of these jurisdictions, and in particular the US states concerned, have adopted a legalisation system which gives market dynamics a significant role to play in regulation and, consequently, makes room for private entrepreneurship. The first evaluation data made available in certain countries or jurisdictions cannot, therefore, automatically be transposed to Luxembourg, which has specific forms of use and will adopt its own method of regulation.

In general, international studies show that it is necessary to go beyond analysis of the prevalence indicator alone in order to fully understand the impact that a change in access to cannabis, or any other psychoactive substance, may have (e.g. number of medical emergency episodes, hospital admissions and treatment requests related to cannabis use). In addition, comparisons of the situation before and after the pilot project are required. Consequently, a research proposal, including an analysis of the initial reference situation (baseline), is required.

Age criterion

The question of the minimum age of legal access to cannabis presents the legislator with a dilemma that can only be resolved through compromise. There is no single, perfect answer to this question. In fact, setting the age limit for legal access at 18 does not fully take into account the results of scientific research on brain development and the potential associated damage. On the other hand, setting the minimum age at 21 or 25 means depriving the segment of the general population in which cannabis use is most widespread (including minors), of legal, quality-controlled cannabis, and exposing it to the supply and risks of the residual black market. In addition, clashing with the criminal justice system can have consequences for the educational, employment and social inclusion chances of many users. Setting the age of legal access to cannabis at 21 or 25 could also result in alcohol being perceived as less harmful by young and old alike, whereas most analyses suggest the opposite is the case.

In addition, in our societies, the age of majority represents individual responsibility[3]. It may, therefore, seem questionable, or even contradictory, to hold 18-year-olds responsible for every aspect of their lives apart from their choice to use cannabis.

Simply introducing a legal age limit of 18 years for legal access to cannabis for non-medical purposes will not simultaneously remove the attraction of this substance and its effects on young people and minors, especially as many young people already use cannabis before the age of 18.

It could be argued that setting the age criterion for acquiring cannabis for non-medical purposes at 18 could leave young people under the age of 18 who are looking for cannabis with no choice but to seek it on the black market. This may even encourage drug dealers to adopt more targeted and aggressive sales strategies towards people under the age of 18 in order to compensate for the loss of revenue caused by the introduction of legal access to cannabis for non-medical purposes for adults aged 18 and over. Canada has tried to address this situation by decriminalising the possession of up to five grams of cannabis for young people under the age of 18, where it is for personal use and is not linked to cannabis trafficking.

If the risk of a possible increase in traffickers using aggressive sales techniques targeted at minors, is combined with the possibility that some adults may obtain cannabis legally and sell it to minors, the risk of increased exposure of minors to cannabis cannot be eliminated, which in turn may lead to an increase in use, and frequency of use, in a population considered particularly vulnerable from a psychological and physical point of view.

In fact, the use of cannabis with a high THC content is more risky the earlier in life a person takes it and it can negatively affect brain development in children, adolescents and young adults. It is currently accepted that the main developments in brain maturity and connectivity are complete around the age of 25. The potential harm caused by regular use of cannabis with high THC content is considered to be at its greatest before this age.

What’s more, cannabis use in adults is not without risk. It can lead to desocialisation, or even trigger psychotic decompensation in predisposed individuals (family history of psychotic disorders) and depending on the method of use (e.g. early use of cannabis, use of cannabis high in THC and low in CBD). It is worth noting that these risks increase with the THC and CBD content of cannabis, which has been steadily rising and falling respectively over the last decade.

In addition, perception of the risks associated with cannabis use may diminish and, as a result, cannabis use may be normalised or trivialised. It therefore seems useful to explain to the public that access to cannabis is not regulated in the pilot project because it is risk-free, but because the negative side effects of a punitive response to cannabis use are greater and because it is reasonable and necessary to consider whether other approaches might not be better suited to reducing health and safety risks and associated illegal activities.

The important thing about setting the legal age of access at 18 – which, let us remember is, in the case in point, nothing more than one tenable compromise – is not to punish offending minors indiscriminately, but to take advantage of this opportunity to discuss with the young people concerned their use, or even high-risk use, and the context of this use, and to make it a fully fledged prevention and risk-reduction tool.

In any event, the young people in question should be involved in early interventions in groups, or on an individual basis, to make them aware of the risks associated with their use of cannabis or other drugs.

Offers of prevention, (early) counselling and care for young people are available nationwide. These have been developed in close cooperation with the Ministry of Health, the Public Prosecutor’s Office and specialist services and are designed specifically for interaction with young people, particularly where an offence has been committed, allowing them to access a structured programme to help them come to terms with the current situation and to develop their skills and evaluation capabilities.

In addition to these measures, it is essential to develop and implement a comprehensive information, education, prevention and communication strategy specifically targeting young people (see chapter on prevention).

Road safety

Legal access to cannabis may have implications for road safety, although driving under the influence of cannabis is already an observable phenomenon today.

It is important for any change in approach and any legislative change in the area of legal access to cannabis to be accompanied by a coherent information, prevention and care strategy. The aim is to increase drivers’ awareness that driving under the influence of cannabis involves risks both for them and others.

In accordance with the law of 14 February 1955, on traffic regulation on all public highways, any driver of a vehicle or animal, as well as any pedestrian involved in an accident, whose body contains a serum THC level of 1ng/ml or more, shall be punished by imprisonment of between eight days and three years and a fine of between €500 and €10,000, or one of these penalties only.

Public health authorities will be responsible for supporting policing activities through education and awareness-raising of the dangers of driving after using cannabis.

Likewise, a simultaneous stepping-up of the law enforcement response to any activities outside the framework of the pilot project would seem appropriate. In addition, a research and monitoring system must be set up to validly measure the impact of the measures adopted in order to be able to progressively assess their feasibility and the possible need to extend them, or even to reconsider or develop them at a later date.

Currently, the Highway Code provides for a critical threshold of 1 ng/ml of THC in the bloodstream.[4]

It is recommended that expert advice be sought during the legislative process. This is to ensure that the measures in place are based on up-to-date, valid and robust scientific evidence that reliably detects whether the driver is fit to drive a vehicle or whether the driver’s faculties are impaired.

Safety at work/high-risk jobs:

Collective labour agreements, internal company regulations, etc. deal in various ways with being under the influence (of alcohol or other psychoactive substances) in the workplace. It is necessary to check whether cannabis use is covered by these provisions, bearing in mind that there is currently no simple method that can be used by non-experts to detect, at first sight, and without additional means of detection, someone who is under the influence of cannabis, unlike someone who is under the influence of alcohol (breath, slurred speech, etc.).

It is also recommended that expert advice be sought during the legislative process.

1.4.3 Financial and banking industry

The pilot project for legal access to cannabis for non-medical purposes could have an impact on the financial sector, in particular, due to European and international regulations in force (especially to combat money laundering), as well as the rules imposed by the United States. The Patriot Act prohibits US companies from having contact with foreign companies involved in, among other things, the trafficking of controlled substances, such as cannabis. In Uruguay, for example, banks have stopped all transactions connected with the sale of cannabis, even though sales are managed by state-run pharmacies, for fear of no longer being able to carry out transactions with the United States.

At this stage, the same difficulty does not appear to have been experienced on the Canadian side. Banks are, however, reportedly still very cautious and try to keep any cannabis-related transactions strictly separate from their US transactions. It is, therefore, worth examining this point in greater depth in order to determine the possible impact of the pilot project for legal access to cannabis for non-medical purposes on the financial and banking sector in Luxembourg.

With the pilot project in question, accepting customers operating in the cannabis-related production and/or marketing sectors, even if these activities have been legalised, is a matter for the banks’ own commercial policy. Those concerned cannot, therefore, be guaranteed an account.

As for the implications for compliance with international anti-money laundering rules, this point remains to be explored in greater depth as the models under consideration are put into practice.

In any event, all operators in the future regulated cannabis sector will be bound by a set of existing anti-money laundering rules. These include the obligation to conduct an assessment of the specific money laundering risks associated with the sector (e.g. cash, fraud, unlicensed traders and producers, etc.), taking into account the variables of the national economy and its different sectors, to determine the degree of risk that the sector(s) may pose, or to understand how these money laundering risks may affect the national or even supranational economy.

Where risks are identified, it is then the responsibility of the operators concerned to adapt their behaviour accordingly and to mitigate the risks involved by taking appropriate measures to limit these risks. An appropriate measure in this context would be to restrict, if not completely prohibit, the use of cash for all regulated cannabis-related transactions.

Apart from this specific risk assessment, operators in the cannabis field must also comply with a set of rules that apply to all professionals, such as customer due diligence, a procedure for establishing business relationships (professionals must avoid any business relationship with customers who do not wish to be transparent), the obligation to keep documents (for at least 5 years), to monitor vigilance, to report suspicions to the Financial Intelligence Unit (FIU), to have adequate internal organisation and to put in place written internal control and communication procedures, to proactively cooperate with the competent supervisory authorities, to appoint an internal manager and to provide adequate training to its employees.

Existing administrative and criminal penalties will also apply to those involved in the regulated cannabis sector.

1.4.4 Cannabis products with <0.3% THC

In recent years, many EU Member States, including Luxembourg, have seen the emergence of shops selling flowering tops, and other products extracted from cannabis plants, with a THC content of less than 0.3%.

In the context of, and in advance of, the recommended national pilot project, this aspect should also be managed to ensure the compatibility of these cannabis products with the approach described in the national pilot project for legal access to cannabis for non-medical purposes.

As a result, a dedicated interministerial working group has been set up to determine to what extent adjustments to the legal framework would be necessary.

1.4.5 Industrial hemp sector

The pilot project for legal access to cannabis for non-medical purposes could present new opportunities for industrial hemp cultivation in Luxembourg.

Hemp is one of the oldest plant species cultivated by humans. It was grown as far back as 4000 BC. This plant has also been grown in our region for thousands of years, not only for the production of cloth and rope (fibres), oil for food and other uses (seeds), but also for use as a natural medicine (flowers). In 1865, for example, industrial hemp cultivation in Luxembourg extended to some 700 hectares and was by far the most important oilseed and industrial crop in our country at that time.

As a result of developments in organic and pharmaceutical chemistry at the beginning of the 20th century, the products of hemp cultivation, such as fibres and flowers, had to compete with synthetic products, which led to the decline of industrial hemp cultivation in Europe and particularly in Luxembourg. After the First World War, the decline in industrial hemp accelerated dramatically until the plant, with its many advantages and potential uses, disappeared from Luxembourg completely.

The cultivation of industrial hemp only reappeared in our country about 25 years ago, following an initiative launched by several farmers who were looking for alternative crops to diversify their production and income. As a result, a network of several producers, involving cooperatives and private companies, based on the cultivation of industrial hemp with a low THC content (< 0.3%) and on the food value of the seeds and flowers, has since been successfully established. In addition, alongside this network with its very varied product range, the Chamber of Agriculture, in partnership with the FIL (Fördergemeinschaft Integrierte Landbewirtschaftung FIL Asbl) as part of the EFFO (Effiziente Fruchtfolgen) project, as well as the Agriculture Technical Services Administration (ASTA), set up industrial hemp trials on several experimental sites to study certain aspects of this crop with a view to helping to relaunch this ancestral plant, which has many advantages, both for the circular economy and for environmental protection, as well as for farmers and users.

In fact, this government’s coalition agreement explicitly provides for the development of industrial hemp in protected areas: “New crops, such as flax and hemp, present opportunities in a number of economic sectors as well as offering real added value for the environment. These crops will, in particular, be encouraged in protected areas”.

As a result, industrial hemp, which had been forgotten for more than a century, could once again have a major role to play in agriculture in Luxembourg and beyond because, as far as the Greater Region is concerned, intensive efforts are being undertaken to promote hemp fibre, also opening up opportunities for cooperation and outlets for Luxembourg producers.

Product varieties

Industrial hemp can be the basis for a wide range of products such as oil (food for human consumption, animal feed), fibre (textiles, insulation/construction, pellets/heating), hemp seed cake (solid residues obtained after extracting the oil from hemp seeds and intended for animal feed), flowers and flower extracts rich in CBD, (food for human consumption and animal feed). As a result, industrial hemp has the potential to become a key element of the bioeconomy and the circular economy, provided that intelligent and full use is made of the very many possibilities it offers i.e. stalks for producing fibres and hemp shives (the woody part of the hemp obtained and separated after scutching the fibre) as by-products, seeds for oil and hemp seed cake produced as by-products and flowers, and flower extracts (especially those rich in CBD) with numerous potential outlets.

This cascade use of industrial hemp, which is in line with how this plant was used traditionally for thousands of years, is not only sustainable and resource-efficient, but also recognises the fact that only full use of hemp, and all its by-products, will ultimately ensure the profitability of the industrial hemp sector.

Currently, more than 60 varieties of industrial hemp (with a low THC content < 0.3%) are already registered in the European Union (EU) Common Catalogue of Varieties of Industrial Plant Species (EU) and so are authorised for cultivation in the EU.[5] It is worth noting that outdoor open-field cultivation and the resulting flowers are not suitable for use in the cannabis products provided for within the context of the pilot project for legal access to cannabis for non-medical purposes.

Potential for the agricultural sector

Agriculture in Luxembourg, as elsewhere in Europe, is lacking in plant protein production and faces enormous challenges in protein autonomy. The use of hemp seed cake, which is very rich in protein, could help reduce national dependence on imported products. CO2 sequestration, as a result of the use of hemp fibres and shives, significantly increases the ecological balance of industrial hemp and is another opportunity for agriculture to join in the effort to mitigate greenhouse gases. The benefits of hemp in protecting soil and water are well known. Hemp could, therefore, become a crucial link in the crop-rotation chain.

Hemp only requires moderate nitrogen fertilisation and the 600-650 litre watering requirements are generally covered by the usual rainfall in Luxembourg. The deep roots of industrial hemp mean that the crop continues to grow when many other crops are already under considerable water stress. These deep roots have additional advantages in that they improve the biological activity of the soil and protect against soil erosion. The plant can also be grown on almost any type of soil in the country.

As a result of strong early growth, weeds barely invade the hemp, so fields are naturally weed-free during, and after, the cultivation of industrial hemp. Consequently, herbicide applications are very much reduced, or non-existent, for two years in a row. An industrial hemp harvest means that winter wheat can be grown under ideal conditions on weed-free plots as the next crop in the rotation.

Since the cultivation of hemp, for which neither weeds nor pests are a major problem, requires almost no use of plant protection products, it could partly replace rapeseed, another oilseed crop, the cultivation of which is declining, not least because of the great difficulties involved in protecting it from weeds and pests.

Better still, the incorporation of industrial hemp, which has no links to other plant species grown in Luxembourg, such as wheat, rape, barley, maize, etc., into existing agricultural rotations, will also have a positive effect on the health status of the follow-on crops, as hemp does not transmit harmful organisms to these crops and, by smothering weeds, leaves the fields weed-free for the follow-on crop. The cultivation of industrial hemp can, therefore, reduce the use of plant protection products throughout the entire crop rotation. As a result, industrial hemp also works well for crop rotation in organic farming.

Ultimately, the cultivation of industrial hemp not only expands the range of agricultural rotations which benefits the environment, in particular, by conserving water resources, but also increases indigenous protein production for animal feed, as well as offering farmers the chance to diversify and increase their income, provided that the industrial hemp is used in its entirety.

Up- and downstream potential for the sector

Alongside the primary agricultural sector, the development of industrial hemp cultivation could also have a positive impact on related up- and downstream sectors (seed production and certification, oil production, storage and production of concentrated animal feed, agricultural machinery, variety trials, research and development, small-scale production of industrial hemp products, renewable energy, heating fuels, etc.).

Potential for other sectors

In addition to the societal gain associated with direct sustainability benefits (soil, water, CO2 sequestration, etc.), the production of a range of fibre-based products for construction and insulation will have a positive effect on our carbon and ecological footprint across the nation. There is enormous potential in the use and extraction of industrial hemp flowers which could provide new sources of income for farms and specialist companies. In this regard, it would be advantageous to harmonise EU legislation on the commercialisation and use of industrial hemp flowers and flower extracts. The use of field-grown flowers offers the added benefit of not requiring the high energy input associated with indoor growing systems (intensive artificial lighting, heating) normally recommended for growing cannabis for medical and non-medical purposes.

[1] Upon examining a series of WHO recommendations on cannabis and its derivatives, the UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs decided to remove cannabis from Schedule IV of the United Nations Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs of 1961, where it was listed alongside other substances, including heroin, that were considered to have no significant therapeutic benefit.

[2] Cerdá, M., Wall, M., Feng, T., Keyes, K. M., Sarvet, A., Schulenberg, J., O’Malley, P. M., Pacula, R.L., et al. (2017). Association of state recreational marijuana laws with adolescent marijuana use. JAMA Pediatr, 171(2):142-9. DOI:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.3624

[3]Anderson, M., Hansen, B., Rees, D., Sabia, J. J. (2019). Association of Marijuana Laws with Teen Marijuana Use. JAMA Pediatr., 173(9):879-881. DOI:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.1720

[4] Ministry of Sustainable Development and Infrastructure (2016) Highway Code, General Plan, Article 12, paragraph four. Luxembourg: Ministry of Sustainable Development and Infrastructure. Available at: http://data.legilux.public.lu/file/eli-etat-leg-code-route-20161028-fr-pdf.pdf

[5] European Commission (2019) European Plant Variety Database. Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/food/plant/plant_propagation_material/plant_variety_catalogues_databases/search/public/index.cfm?event=SearchVariety&ctl_type=A&species_id=240&variety_name=&listed_in=0&show_current=on&show_deleted

PART II

LUXEMBOURG MODEL FOR THE PILOT PROJECT FOR LEGAL ACCESS TO CANNABIS FOR NON-MEDICAL PURPOSES

It is proposed that access to cannabis for non-medical purposes should be regulated by a rigorous and robust pilot project tailored to meet the Luxembourg’s specific needs. This fixed-term pilot project must be able to meet the challenges of the approach and achieve the objectives sought.

It should be noted that the pilot project for legal access to cannabis by the state differs from simple liberalisation, an approach where the regulation of supply and demand is supposed to be ensured by market forces and dynamics, with the state contenting itself simply with supervising market access, reducing informational asymmetries and defining the rules of “healthy” competition.

In terms of strategy for the creation and rollout of the pilot project for legal access to cannabis for non-medical purposes, the policy approach is to proceed in stages and to develop a specific approach to cannabis for non-medical purposes.

The first stage, bill No. 8033 amending the amended Act of 19 February 1973 on the sale of medicinal substances and the fight against drug addiction, was introduced on 22 June 2022. The legislative process is currently in progress.

With its risk reduction and crime prevention approach, the bill has a dual objective:

On the one hand, any person of legal age will be allowed to grow up to four cannabis plants, at home, per household, for personal use, exclusively from seed. It is worth noting that plants must be kept out of public view. Personal use in private will be allowed. If the place of cultivation is non-compliant or if the number of plants grown at home is exceeded, criminal penalties will apply.

On the other hand, there are plans to abolish criminal penalties for small quantities of cannabis (< 3 grams) in public. Less complex and swifter criminal proceedings will be introduced for adults in public possession of, or transporting and acquiring, no more than 3 grams of cannabis, or its derivatives (including mixed products). The bill reduces the range of fines to between €25 and €500 with the option for the Grand Ducal Police to issue a warning with a €145 fine. Use in public is still banned.

It is worth noting that this legalisation of self-cultivation and private use is a first step, pending finalisation of the overall concept to counteract the black market and regulate the illegal trade in cannabis. As appropriate, this first step will need to be reviewed and adapted, depending on the final system selected.

When drafting the bill implementing this concept note, the system introduced by bill No. 8033 will, therefore, be reassessed to ensure consistency between the two systems, particularly with regard to the issue of possession of cannabis in public.

To ensure the quality of cannabis and prevent the emergence of an unregulated parallel market for products of uncertain quality, regulations on the packaging and physical sale of cannabis seeds with a future THC content of more than 0.3% for private and personal use, will be put in place.[2]

[1] Bill No. 8033: https://www.chd.lu/fr/dossier/8033

[2] Draft grand-ducal regulation amending the amended grand-ducal regulation of 26 March 1974 setting out a list of narcotics.

At a later stage, the transition to legal access to cannabis for non-medical purposes will be ensured [1] and the following minimum criteria and conditions will have to be met:

- Be domiciled in Luxembourg: Actual residence in the Grand-Duchy of Luxembourg . This provision is intended to prevent “cannabis tourism”, to limit the potential disturbance caused by an increased influx of customers from all sides, and to increase acceptance, or even reduce fear, resistance and criticism from neighbouring countries[2];

- Age criterion: Minimum legal age, i.e. 18 years of age;

[1] As stated in the 2018 coalition agreement described in chapter I.1.

[2] In line with the decision of the European Union Court of Justice ruling on the compliance with EU law of a decision of the Mayor of Maastricht prohibiting coffee-shop owners from admitting to their establishments persons who are not actually resident in the Netherlands (Josemans, Case C-137/09).

For use in private only: The ban on taking cannabis and cannabis-derived products will apply to premises open to and/or serving the public, and to any places in which the ban on smoking (tobacco and e-cigarettes) applies. This measured is intended to limit public nuisances; prevent the passive inhalation of harmful, potentially psychoactive smoke by non-users; and to counter the spread and normalisation of cannabis use, and even the perception that it is less risky, among young and not-so-young people. The same rules must also apply to all other cannabis-based products smoked or vaped, in particular those with a THC content of less than 0.3%.

Maximum monthly and daily quantities: Given the domestic context, it is recommended that the monthly threshold should not exceed 30 grams of dried cannabis per customer. In addition, dispensaries will have to ensure, by means of a computer system common to all outlets, that the maximum quantity of 5 grams per day, per purchase and per customer, is not exceeded. These quantities purchased must be exclusively for personal use.

In order to make it easier to detect violations of the pilot project and ultimately ensure that it can be applied on a permanent basis, the working group believes that a distinction should be made between cannabis of legal, and illegal, origin. Relevant biomarker methods will have to be identified in order to determine, if necessary, the origin of the cannabis, bearing in mind the need for safety for the end-user and the importance of the price of legally available products remaining competitive with those for sale on the black market.

All relevant policies relating to smoking or drinking alcohol in the workplace should be adapted to incorporate the consumption of cannabis for non-medical purposes. In addition, a zero-tolerance rule should be applied to certain professions when carrying out their professional activity, such as pilots, police officers, surgeons, prison staff, professional drivers etc.

The working group recommends that the pilot project be accompanied by a scientific evaluation consisting of a pre- and post-implementation analysis based on validated scientific indicators. This scientific evaluation will be carried out in close collaboration with the EMCDDA and its National Focal Point, and with various public health research institutions. In addition, and as part of a general evaluation, these research institutions, with the support of the Luxembourg National Focal Point of the EMCDDA, will publish a final report on the first seven years after legal access to cannabis for non-medical purposes was introduced. Within this context, it is recommended that the scientific evaluation should also be supported by an independent and neutral committee of experts from different disciplines. The final research evaluation report should, therefore, include the conclusions of the evaluation exercise and, where appropriate, recommendations to be made to the government. It remains to be seen how long the committee will have to complete its evaluation and submit its report to the government before the scheduled end of the pilot project

After receiving the final evaluation report, the government will have a set amount of time, which is still to be determined, to form an opinion on the report and how it wishes to follow up the results and conclusions of the evaluation.

The aim of such an evaluation will be to see whether the approach taken can improve public health protection nationally, in particular, by controlling the quality of products taken by large numbers of the general public, and whether the new prevention strategies can limit use, stem revenue flows and the growth of organised crime, free up capacities and resources for reducing supply and combating organised crime, and reduce the contact between users and criminal circles that has, until now, been unavoidable. In fact, the current situation is not satisfactory for the reasons set out above and it would, therefore, seem fair, and indeed necessary, for the government to work towards finding solutions that are more likely to achieve the desired goals, based on scientifically valid data.

The scientific evaluation will be based on a baseline analysis of the current situation, during the period prior to the implementation of the national pilot project. The baseline data will then be supplemented by periodic analyses for the post-implementation period, in close collaboration with interdisciplinary experts, in order to 1) determine whether the national pilot project scheme is in line with its indicators and targets, 2) monitor emerging trends and their impact on public health, including changes in cannabis use and use-related behaviour, and 3) acquire new evidence-based knowledge.

In order to evaluate and monitor the impact of the national pilot project, six core targets with first, second and third priority indicators for evaluation and monitoring were selected. These were identified mainly by the working group through an extensive literature search and in collaboration with the EMCDDA in order to assess the drug situation and the potential impact of different legal and regulatory changes.

Each indicator associated with one of the six targets was assessed to see to what extent national data and information sources are currently available, the need for international data (EMCDDA, UNODC, etc.), as well as the timeframe for data collection (short, medium or long term) and its relevance in terms of achieving the future regulation’s objectives. The following non-exhaustive list of key epidemiological indicators is proposed:

- Identifying and monitoring factors associated with cannabis use, including psychosocial motivations and determinants e.g. risk perception, social attitudes and norms, socio-economic factors and mental health disorders

- Identifying and monitoring the prevalence of cannabis use and patterns of use among the general population, including vulnerable populations (e.g. groups with low socio-economic status, young people, those experiencing discrimination as a result of their gender, individuals with psychiatric co-morbidity (especially psychotic), etc.)

- Monitoring the prevalence of high-risk cannabis users

- Monitoring treatment provision and the proportion of high-risk cannabis users (cannabis as the main product) entering treatment, both in terms of access and treatment outcomes

- Identifying and monitoring changes in usage and possible impacts (including negative impacts) associated with the prevalence of use of other controlled and regulated psychoactive substances (including alcohol, tobacco, medicines and illicit drugs such as opioids)

- Assessing and monitoring morbidity and adverse effects associated directly and indirectly with cannabis use

- Collecting data and monitoring healthcare use directly and indirectly related to cannabis use (e.g. number of medical emergency episodes and hospital admissions related to cannabis use)

- Identifying and monitoring the social (family, professional, legal) and economic (loss of productivity, employment, school drop-outs, etc.) consequences of cannabis use

- Identifying and monitoring the consequences of the redeployment of policing activity

These indicators, in line with the objectives of the pilot project, will help to provide objective and reliable informationon cannabis use, its determinants and consequences in order to assess trends and developments in the supply and demand for cannabis. This work will make it possible to conduct a needs analysis to facilitate the development of targeted policy measures, including public health and public order intervention programmes.

The scientific evaluation will require one or more national mixed-method studies to collect data relating to the selected epidemiological indicators. For example, a general population survey (GPS) specifically dedicated to drug use and perceptions should be set up. The data currently available do not allow for a sufficiently nuanced assessment of the behaviours and perceptions associated with drug use prior to any change in the current regulatory framework, nor do they allow for measurement of the resulting effect on these indicators.

A general population survey could, therefore, cover and assess a large number of indicators. One example is the indicator of prevalence of cannabis use in the general population, for which measuring different rates of prevalence of cannabis use, including lifetime prevalence, past year prevalence and last month prevalence, is recommended. Analysis of non-use, past use and current use will make it possible to identify “new users”. The impact of usage will be one of the key indicators for steering and adjusting the planned policy. Other variables to be considered are socio-demographic factors, age at which cannabis use starts, frequency of use, psychosocial factors, etc. The general population survey should be supplemented by targeted studies that provide more detailed data on current cannabis users and (future) growers, e.g. cannabis users’ habits, quantities taken, usage patterns (including methods of taking cannabis), type of product taken (CBD-dominant/THC-dominant), intentions to grow cannabis plants at home, sources of cannabis acquisition (legal versus black market).

Establishing a representative general population survey supplemented by targeted studies will boost the availability of national data and statistics on the drug situation. The information gathered will facilitate study of the drug phenomenon, understanding of the impact of drug-related policy changes, identification of priorities and better planning of responses. Lastly, the general population survey will support the EMCDDA’s key indicator on prevalence and patterns of drug use, which makes it possible to collect and interpret harmonised and high quality European data.

This survey will require a nationally representative probability sample of people aged 15-64 and residing in Luxembourg. EMCDDA guidelines and European model questionnaires will be used to develop the questionnaire.

The evaluation studies will help to establish a baseline of specific indicators that are relevant in the context of the yet-to-be-implemented cannabis regulations. For example, it will be necessary to estimate consumption patterns and habits, motivations, attitudes and perceptions of risk, supply behaviour, and the prevalence of cannabis-related addictive disorders.

In addition, it is important to monitor trends in supply reduction indicators and the market for illegal psychoactive substances, including the number of cannabis seizures, quantities seized, street prices, types of cannabis products seized, THC concentration and contaminants in cannabis products seized in Luxembourg.[1] In addition, judicial and penal measures will be monitored, including the number of summons (arrests and charges) for cannabis-related offences. The number of fatal and non-fatal road accidents and cannabis driving offences will also be assessed.

Wastewater analysis can provide an additional source of data to qualify, or even validate, the survey data.

In addition to analysing the impact on public health, assessing the impact, before and after the pilot project, from an economic perspective is recommended. The economic impact assessment will focus on health economics approaches and a cost-of-illness study. This study will include, among other things, the costs to the health sector (direct costs), the value of lost productivity (indirect costs), and intangible costs.

Finally, a process evaluation of the national pilot project for legal access to cannabis for non-medical purposes should be considered. This evaluation will determine whether the different components of the pilot project were carried out as planned (fidelity) and whether its objectives were achieved. The process evaluation will generally review stakeholders’ experiences and help to determine which elements of the new pilot project are working well in practice, how well the pilot project is achieving its objectives, and which elements should be modified for improvement.

Evaluation of all aspects of the situation before, and after, the implementation of the pilot project will provide new scientific, theoretical and practical knowledge about cannabis use and regulation. The pilot project and its outcomes should be subject to ongoing monitoring and interim evaluations.

This evaluation process should be accompanied by a national research strategy, possibly in conjunction with international partners. In this way, Luxembourg will contribute to the international scientific community’s efforts to advance knowledge of all aspects of cannabis and to expand the scientific literature on the subject, which is still lacking. This approach will help to develop intervention programmes (preventive, educational, behavioural, psychological) based on scientific protocols and evidence.

[1] N.B. Seizures are not a particularly useful measure of the size of the black market. They are likely to be, above all, a measure of policing activity rather than market size, and the lessons to be learned from them may be distorted by a small number of significant seizures over a period of time.

The importing of cannabis is currently not a viable option. It will therefore be necessary to, right from the outset, plan for the establishment of a national production and marketing chain; given the current lack within Luxembourg of infrastructure for and experience of cannabis cultivation and production within a legal and controlled framework and environment, this looks likely, at the moment, to be a long-term undertaking.

It is recommended that a national control agency for that production and marketing chain be made responsible for oversight of the country’s production and producers and for the purchase of domestically produced cannabis. That option seems the wisest choice with a view to preventing companies’ profit-seeking from conflicting with the primary public health goal of reducing the negative side effects of cannabis use among the population at large. This national agency must be able to ensure the production of enough varieties of cannabis to prevent users from turning or returning to the black market.

During the establishment of the legal framework regulating production, it will be important to conduct a market analysis and determine whether the offering will meet users’ needs, in order to avoid over-/underproduction, or even a negative impact on changes to the ways in which the drug is taken. This goal could be achieved by limiting the number of production permits issued and/or a producer’s total permitted output. In addition, such a measure will contribute to mitigating the risk that legally produced cannabis could be diverted onto the black market.

On the basis of these considerations, it is proposed that producer companies be granted a maximum of two production permits and be able to acquire no more than one permit for a single production site. In order to be able to apply, companies will have to meet the quality requirements laid down by the authorities and the eligibility conditions set out in the specification. The permits will authorise the growing, processing and distribution, under certain conditions, of cannabis for non-medical purposes.

In view of the estimated number of potential users and of the small size of Luxembourg territory, it is estimated that two production sites will be able to meet domestic needs. Since the sustainable and guaranteed production and supply of cannabis for non-medical purposes is a key element of the later stage of the pilot project, this stage must not start until the legal framework regulating the production of cannabis for medical purposes is in place.

The production of cannabis for medical purposes is particularly important as part of a holistic and proactive approach, since the related legal framework being in place will therefore be a precondition for starting the subsequent stages described in the pilot project of legal access to cannabis for non-medical purposes.

The legal framework regulating production of cannabis for medical purposes will therefore serve, subsequently and after the related legal framework is in place, as the regulatory, administrative and logistical basis for establishing the production of cannabis for non-medical purposes.

2.5.1 Varieties of product

It is important to offer a varied range of products on the legal market, in order to meet users’ demand. The varieties of product that may be sold should be set out in the specification for a public tendering procedure relating to the allocation of production permits.

The products to be included must be decided on the basis of what is currently available on the black market and of the risks associated with using different varieties of cannabis. Those risks are closely linked to THC and CBD concentrations, and strongly influenced by the method used to take the drug and the amount taken.

Initially, a range of cannabis flowering-tops and resin products is being considered. Nevertheless, it seems appropriate to supply dispensaries with a range of cannabis varieties (several THC/CBD ratios and terpene profiles) and of appropriate THC and CBD concentrations, in order to ensure the lowest possible probability that users, unable to find the desired variety for sale legally, will turn or return to the black market.

In addition, since certain hybridisation and extraction techniques now make it possible to produce plant varieties or derived products containing very high THC concentrations (e.g. butane hash oil), the varieties and resins supplied by producers must meet the criteria laid down in the specification. The production and sale of pre-rolled cigarettes (joints), containing either tobacco and cannabis or just cannabis, must be prohibited.

2.5.2 General requirements for the producer to meet

It is recommended that producers should meet the following minimum criteria (non-exhaustive list):

- The producer must draw up a project proposal covering growing operations, post-harvest facilities, quality checks, quality-management system and the cannabis varieties (e.g. THC/CBD ratio and terpene profile) that it wishes to grow.

- The producer must guarantee the product quality standards – which have yet to be set out – throughout the production chain (growing, packaging, storage, etc.).

- The producer is responsible for security measures, in particular the completely secure storage of the cannabis, and must ensure a safe and healthy work environment.

- The producer must undertake to use exclusively the tracing software provided by the control agency, as defined in item 7, enabling the route taken by each finished product to be traced, so that the closed cannabis production chain can be properly monitored.

- Cultivation, drying and packaging of the product must take place on the same site, in order to avoid any unnecessary transportation.

- The producer must undertake to make every effort to prevent criminal involvement in the cannabis production and marketing chain and to cultivate no cannabis other than that which is to be sold at the dispensaries authorised under the national pilot project.

- The producer will not be permitted to sell online or deliver to customers’ homes.

- Every available resource is to be brought to bear to prevent the exporting of cannabis for non-medical purposes.

- The producer must meet stringent reliability requirements: the operator, manager and staff must exhibit a high degree of integrity, which will be checked in cooperation with the competent authorities; the THC and CBDcontent allowances of the dry weight – at a given percentage, to be determined – must be clearly marked and observed.

- The production of cannabis-derived products whose THC content deviates in a significant way – which has yet to be defined – from the level stated or required in the regulations should be considered a serious breach of the conditions for granting of the permit.